One of the interesting things about contemporary data visualization is that the field has a deep sense of its own history, but that "professional" historians haven't paid a great deal of attention to it yet. That's changing. I attended a conference at Columbia last weekend about the history of data visualization and data visualization as history. One of the most important strands that emerged was about the cultural conditions necessary to

read data visualization. Dancing around many mentions of the canonical figures in the history of datavis (Playfair, Tukey, Tufte) were questions about the underlying cognitive apparatus with which humans absorb data visualization. What makes the

designers of visualizations think that some forms of data visualization are better than others? Does that change?

There's an interesting paradox about what the history of data visualization shows. The standards for data visualization being good change seem to change over time. Preferred color schemes, preferred geometries, and standards about the use of things like ideograms change over time. But, although styles change, the justifications for styles are frequently cast in terms of science or objective rules. People don't say "pie charts are out this decade"; they say, "pie charts are objectively bad at displaying quantity." A lot of the most exciting work in the computer science side of information visualization is now trying to make the field

finally scientific. It works to bring scientific research into perception from mere style, like the influential and frequently acerbic work of Tableau's

Robert Kosara; or to precisely identify what a visualization is supposed to do (be memorable? promote understanding?) like the work of

Michelle Borkin, my colleague at Northeastern, so that the success of different elements can be measured.

I think basically everyone who's thought about it agrees that good data visualization is not simply art and not simply science, but the artful combination of both. To make a good data visualization you have to both be creative, and understand the basic perceptual limits on your viewer. So you might think that I'm just saying: the style changes, but the science of perception remains the same.

That's kind of true: but what's interesting about thinking

historically about data visualization is that the science itself changes over time, so that both what's stylistically desirable and what a visualization's audience has the cognitive capacity to apprehend changes over time. Studies of perception can tap into psychological constants, but they also invariable hit on cultural conditioning. People might be bad at judging angles in general, but if you want to depict a number that runs on a scale from 1 to 60, you'll get better results by using a clock face because most people spend a lot of time looking at analog clocks and can more or less instantly determine that a hand is pointing at the 45. (Maybe this example is dated by now. But that's precisely the point. These things change; old people may be better at judging clock angles than young people.)

This reminds me of the period I studied in my dissertation, the period in the 1921s-1950s when advertisers and psychologists attempted to measure the graphical properties of an attention-getting advertisement. Researchers worked to understand the rules of whether babies or beautiful drew more attention, whether the left or the right side of the page was more viewed; but whether a baby grabs attention depends as much on how many other babies are on the page as on how much the viewer loves to look at babies. The canniest copywriters did better following their instinct because they understood that the attention economy was always in flux, never in equilibrium.

So one of the most interesting historical (in some ways

art-historical) questions here is: are the conditions of apprehension of data visualization changing? Crystal Lee gave a fascinating talk at the conference about the choices that Joseph Priestley made in his

chart of history; I often use in teaching

Joseph Priestley's description of his chart of biography, which uses several pages to justify the idea of timeline. In the extensive explanation, you can clearly see Priestley pushing back at contemporaries who found the idea of time on the x-axis unclear, or odd to understand.

|

| This seems obvious: so why did Priestley take pages and pages to make the point? |

That doesn't mean that "time-as-the-x-axis" was impossible for *everyone* to understand: after all, Priestley's timelines were sensations in the late 18th century. But there were

some people who clearly found it very difficult to wrap their heads around, in much the same way that--for instance--I find many people have a lot of trouble today with the idea that the line charts in Google Ngrams are insensitive to the number of books published in each year because they present a ratio rather than an absolute number. (Anyone reading this may have trouble themselves believing that this is hard to understand or would require more than a word of clarification. For many, it does.)

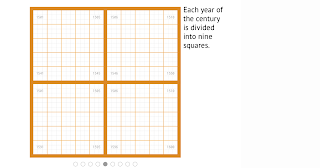

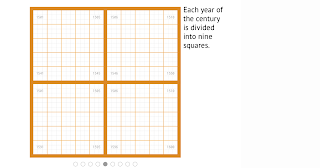

That is to say: data visualizations create the conditions for their own comprehension. Lauren Klein spoke about a particularly interesting case of this, Elizabeth Peabody's mid-19th century pedagogical visualizations of history, which depict each century as a square, divided into four more squares, each divided into 25 squares, and finally divided into 9 more for a total of 900 cells.

|

| Peabody's grid, explanation: http://shapeofhistory.net/ |

There's an oddly numerological aspect to this division that draws it structures by the squares of the first three primes;

Manan Ahmed suggested that it drew on a medieval manuscript tradition of magic squares.

|

| Old manuscript from pinterest: I don't really know what this is. But wow, squares within squares! |

Klein has created a fully interactive recreation of Peabody's visualization online here, with original sources. Her accompanying argument (talk form here), which I think is correct, includes the idea that Peabody deliberately engineered a "difficult" data visualization because she wanted a form that would promote reflection and investment, not something that would make structures immediately apparent without a lot of cognition.

Still, one of the things that emerged again and again in the talks was how little we know about how people

historically read data visualizations. Klein's archival work demonstrates that many students had no idea what to do with Peabody's visualizations; but there's an interesting open question about whether they were easier to understand then than they are now?

The standard narrative of data visualization, insofar as there is one, is of steadily increasing capacity as data visualizations forms become widespread. (The more scientific you are, I guess, the more you might also believe in

constant capacity to apprehend data visualizations.) Landmark visualizations, you might think, introduce new forms that expand our capacity to understand quantities spatially.

Michael Friendly's timeline of milestone visualizations, which was occasionally referenced, lays out this idea fairly clearly; first we can read maps, then we learn to read timelines, then arbitrary coordinate charts, then boxplots; finally in the 90s and 00s we get treemaps and animated bubble charts, with every step expanding our ability to interpret. These techniques help expand understanding both for experts and, through popularizers (Playfair, Tufte, Rosling), the general public.

What that story misses are the capacities, practices, and cognitive abilities that were lost. (And the roads not taken, of course; but

lost practices seem particularly interesting).

So could Peabody's squares have made more sense in the 19th century? Ahmed's magic squares suggest that maybe they were. I was also struck by the similarity to a conceptual framing that some 19th-century Americans would have known well; the public land survey system that, just like Peabody's grid, divided its object (most of the new United States) into three nested series of squares.

Did Peabody's readers see her squares in terms of magic squares or public lands? It's very hard--though not impossible--to know. It's hard enough to get visualization creators nowadays to do end-user testing; to hope for archival evidence from the 19th century is a bridge too far.

But it's certainly possible to hope for evidence; and it doesn't seem crazy to me to suggest that the nested series of squares used to be a first-order visualization technique that people could understand well, that has since withered away to the point where the only related modern form is the rectangular treemap, which is not widely used and lacks the mystical regularity of the squares.

I'm emphatically

not saying that 'nested squares are a powerful visualization technique professionals should use more.' Unless your audience is a bunch of Sufi mystics just thawed out of a glacier in the Elburz mountains, you're probably better off with a bar chart. I am saying that maybe they used to be; that our intuitions about how much more natural a hierarchical tree are might be just as incorrect as our intuitions about whether left-to-right or right-to-left is the better direction to organize text.

From the data visualization science side, this stuff may be interesting because it helps provide an alternative slate of subjects for visualization research. Psychometry more generally knows it has a

problem with WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic) subjects. The data visualization literature has to grapple with the same problem; and since Tufte (at least) it's looked to its own history as a place to find the conditions of possible. If it's possible to change what people are good at reading, that both suggests that "hard" dataviz might be more important than "easy" dataviz, and that experiments may not run long enough (decades?) to tell if something works. (I haven't seen this stuff in the dataviz literature, but I also haven't gone looking for it. I suspect it must exist in the medical visualization literature, where there are wars about whether it's worthwhile to replace old colorschemes in, say, an MRI readout that are perceptually suboptimal but which individual doctors may be )

From the historical side, it suggests a lot of interesting alignments with the literature. The grid of the survey system or Peabody's maps is also the "grid" Foucault describes as constitutive of early modern theories of knowledge. The epistemologies of scientific image production in the 19th century are the subject of one of the most influential history of science books of the last decade,

Daston and Gallison's Objectivity. The intersections are rich and considerably more explored, from what I've seen well beyond history of science into fields like communications. I'd welcome any references here, too, particularly if they're not to the established, directly relevant field of the history of cartography. (Or the equally vast field of books Tony Grafton wrote.)

That history of science perspective was well represented at Columbia, but an equally important discipline was mostly absent. These questions of aesthetics and reception in visualization feel to me a lot like art-historical questions; there's a useful analogy between understanding how a 19th century American read a population bump chart, and understanding how a thirteenth century Catholic read a stained glass window. But most of the people I know writing about visualization are exiles from studying either texts or numbers, not from art history. External excitement about the digital humanities tends to get too excited about interdisciplinarity between the humanities and sciences and not excited enough about bridging traditions inside the humanities; one of the most interesting areas in this field going forward may be bridging the newfound recognition of the significance of data visualization as a powerful form of political rhetoric and scientific debate with a richer vocabulary for talking about the history of reading images.